Borders of extraction

Cultivating Culture | Cultural Cultivation

creating spaces of (ex)change

We are now living in the anthropocene: a world designed by, and for, the human race. We have taught ourselves that 'man' is a force distinct from and superior to 'nature', creating borders between us and them to see fellow species as 'other'. As resources to be objectified and exploited.

Nowhere is this border so defined as between the land and the sea. Entire ecosystems are commodified as 'stocks' to be owned, managed and plundered; normalising the extraction of living animals from the sea in their trillions every day for our tastebuds and profit.

This commodification is naturalised through the romanticisation of seascapes. We visualise fishing communities as places of tranquil tradition; a culture to be celebrated and protected at all costs. Yet separating humans from the ecosystem we are embedded within is destroying the lives of other animals, the environment we all share and threatening our own lives.

Alternatives to animal-based foods exist and the arguments for their adoption is compelling, so why haven’t we changed our approach to production? Food, despite playing an essential, daily part of each of our lives, appears to be the last aspect we are willing to change. It is embedded within our social, cultural and emotional connections: a change to our eating can bring so much more.

A new approach to food production must be envisaged, using spatial design as form of activism: a tool to enable and challenge a shift in our perception and relationship with other species.

This thesis combines the physical infrastructure needed to enable a new system of production with the aesthetic capacity of design to entice, incorporate the new, bring cultural shifts. Monocultural production and spaces of segregation are regenerated to unite producer and consumer, shaping spaces for not only humans but for all species to thrive.

Understanding the process of change as a series of provocations, reminders and inspirations, integrated landscapes of production break down the segregation between land and sea. A series of moments mark the gradual transition from the comfort and familiarity of the land, to the sublime, unknown of the sea; defamiliarising, reorienting, sharing and expanding, pausing, reflecting and diverting.

Food production is reimagined as a plant-based process that anchors habitat and livelihoods for other species within productive spaces for humankind, bringing together human and non-human needs for spaces of co-existence.

Consumption is reunited with production to question the protective romanticisation of fishing communities and culture the growth of new practices that value us all: consumers, producers, humans, non-humans and the environment that supports us all.

Graduation Thesis, TU Delft

June 2019

Final booklet published in full via issuu

KEY CONCEPTS

cross-species co-habitation

architecture as activism

design and behavioural change

socio-spatial justice

climate and food justice

“Change is cumulative. For each person who reaches a pivotal shift in behaviour, there has been a series of stories, moments and interactions leading them to this decision. Activism must take the form of a series of gentle, guided and repeated messages”

– Dr Melanie Joy, 2017

Salmon farming vs. seaweed cultivation

The commodification of 'nature' and other animals has led us to treat sentient beings as objects, seeing them as resources to own, products to sell and bodies to farm.

Humans have converted almost 50% of all habitable land mass into agricultural land to create vast swathes of monocultured space, destroying the original diversity of habitats to design spaces purely for human use.

Non-human animals are designed out of our landscapes, with only certain species designed in via boxes of segregated, agricultural land. 96% of all mammals on Earth are now comprised of humans and those animals we farm as livestock - just 4% are wild.

Even as awareness of the damage our food production causes is growing, fish are still left out of the ethical and environmental arguments for a plant-based diet. Occupying this separate zone of the 'other' - the sea outside the border - we find it even harder to empathise with fish than other animals and still mostly speak of the damage of the fishing industry in terms of 'overfishing', stock levels and 'sustainable sourcing'.

Our monocultured approach to land-based agriculture is being transferred to the seas as aquaculture recreates the toxic waste, antibiotic dependency, loss of biodiversity and mass incarceration of other animals that we have on the land. Our food system is broken. It relies on the extreme exploitation of nature and other animals and is quickly ceasing even to serve humans.

Yet the cultivation of seaweed holds a fantastic potential. It offers the same nutritional profile for humans as animal proteins. It can be grown and harvested as part of diverse, regenerative habitats that support the rebalancing of nutrients and repopulating of waters by other animals. It can be grown seasonally, in small-scale operations and harvested lightly.

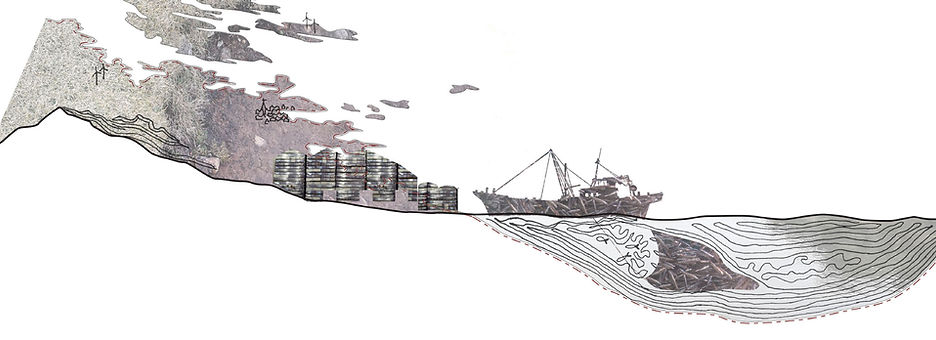

Scalloway is the historical fishing capital of the Shetland Isles, 12 hrs off the coast of mainland Scotland. Once romanticised as a quaint fishing town, industrialisation has moved towards intensive aquaculture and centralised processing in Lerwick, where a huge factory handles 60 tons of fish every hour. Scalloway is left stuck in a tired nod to its past.

The pier reaching out into the centre of the harbour is taken as a symbolic transition from the old to the new, from land to the sea, from tradition to opportunity. A cluster of buildings are regenerated, anchoring a nudge towards new cultures within the vernacular of the familiar.

Aquaculture and the fishing industry in the Shetland Isles

Kombu culture - the culture of food

The agency of spatial design as a tool to encourage behavioural shifts is explored via three complementary routes of power.

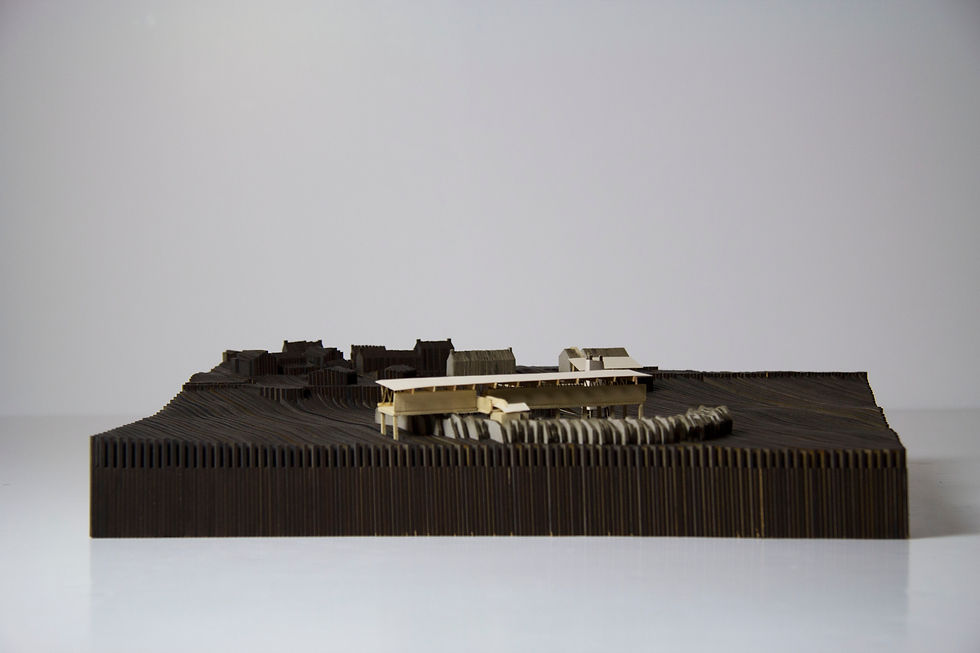

The technical capacity of architecture to provide a new infrastructure is employed to create the physical substrate needed for a new method of food production. A series of pyramidal reef modules are stacked in tessalating triangulated structures for seaweed growth, the form designed to prevent human access beyond the top two layers, preventing overharvesting and reclaiming space for other species. Recycled aggregate, concrete and local rock form a rough substrate to accommodate life at all trophic levels.

The aesthetic power of architecture is recognised as a powerful tool of human creativity, enabling us to celebrate culture, communicate ideas and signal a sense of space. Local vernacular forms of agricultural oast houses are referenced in the drying process and reclaimed materials from fishing boats unite the importance of the familiar with the allure of the new. Central within the bay, interventions wind out into the sea, creating new landmarks of change and inviting the exploration of new cultures.

The socio-spatial capacity of architecture to direct us, bring us together is employed to create spaces of cross-species co-habitation, intersecting the human experience with the lives of other animals. Views are set up to connect visitors with the lives of birds in the sky and fish below the surface, providing the opportunity for a new relationship beyond their commodification. Thresholds are carefully managed to create moments of pause, of reflection, of transition and change.

The visitor is invited to reframe their view, to step back from a position of superiority above, where the sea can seem like one big resource and position themselves within an embedded ecosystem, many individuals as one.

From one to many: reframing our relationship with others

Territorial Reclamation

Spatial design is used as a form of activism to reclaim territory for other species.

A series of productive reefs create a network of regenerative habitats, adopting an organic and distributed formation to oppose the hegemony of anthropocentric, monocultural production

From Sea to Land

The growing urbanisation of seascapes can become an opportunity to find new approaches to productive foodscapes.

Lessons learned from a regenerative, inclusive and biodiverse seaculture can be brought to our practices on land, repairing our monocultured relationship to agriculture and revaluing the culture of production

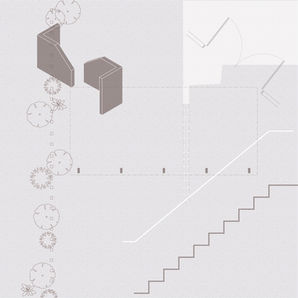

Site Plan

Production, processing and consumption intersect to blur the division between producer and consumer.

Access to food, company, knowledge and territory is available to all, human and non-human

A Series of Interventions

From Land to Sea

From Sea to Land

Long Section - Drying Tower

The triangulated structures of the drying tower and the colonnade grow from pyramidal form of the reef modules to become beacons of change.

The aesthetic power of design uses the idea of a landmark to entice, encourage us to try something new.

Long Section - Teahouse

The zone of consumption, the teahouse, is embedded withing the zone of production, the reef.

Processing Route

The potential of seaweed is maximised to produce edible plant proteins, energy in the form of biofuel and fertiliser to feed back into a more sustainable agriculture on land.

The whole process is visible and celebrated with the community.

Drying Tower

The path takes a change of direction here, giving the opportunity for the visitor to pause and connect with the journey, the sky and seabirds above and the sea and fish co-habiting below.

It forms a space of cross-species co-habitation and decommodifies our relationship to fish.

Drying Tower

The path takes a change of direction here, giving the opportunity for the visitor to pause and connect with the journey, the sky and seabirds above and the sea and fish co-habiting below.

It forms a space of cross-species co-habitation and decommodifies our relationship to fish.

Processing the Visit

The colonnade and path take the angled language of the reef, cutting through the linearity of the processing plant.

Glimpses of what lies ahead are framed throughout the journey, engaging and drawing visitors through.

Space of Production

The permanent concrete platformhosts a spine of services year round, with the colonnaded canopy creating the community walkway.

Temporal structures can then appropriate the space according to production needs, seasonality, weather and demand.

Interspecies Intersection

Moments of shared space across species encourage connection and empathy.

The creative agency of architecture and design can be used to lift us all, no matter the species.

Structural Strategy - Teahouse

The external shell is cast on shore, before being floated out and secured to the reef modules. Terraces are then poured in situ at low tide, the concrete setting organically and in response to the whims of the sea.

layers of insulation are then laid, with the internal leaf of concrete cast in situ, the finish subtly differentiating the interior from the exterior.

Wider Relevance & Future Application

The potentials of seaweed cultivation are plentiful - from habitat regeneration and transition to a plant-based diet, to energy production, bioremediation, nature-based coastal defence, cultural and economic transition...

The intervention in Scalloway harbour is taken as a precedent, the key agencies of architecture identified to be incorporated and contextualised more widely.

The core concepts remain. A visible and accessible infrastructure of production. The celebration of regenerated culture and vernacular tradition. Their unity via visual and physical connectedness, regardless of species.